Basil Davenport, an author and literary critic for the New York Times, once said that “Science Fiction is fiction based upon some imagined development of science, or upon the extrapolation of a tendency in society.”[1] Indeed the technologies presented in many science fiction stories examine the possibilities and implications of new devices, machinery and other practical applications developed from scientific knowledge. Unique to the genre is the possibility that some of these speculative products of the imagination may become realities. Examples include now commonplace things such as space stations, mobile tablets, video-calling and moisture farming, all of which were once just fictional concepts. Occasionally, the real-world technology gets invented first, and science fiction authors ponder and elaborate on how these developments may be used. More importantly, they speculate on how technology could affect the human condition, both for good and for ill.

Filipinos have been writing Science Fiction for 70+ years. Here are 10 interesting speculative technologies that are worth contemplating — especially since they were used in the context of a Philippine setting.

Note that this list is not comprehensive and selects only those technologies that are realistic (based on existing or near-future technologies), or based on far-out concepts that do not violate generally-accepted scientific laws. Excluded are technologies used purely for plot-device purposes or have no actual scientific basis (e.g. the gravity disruptors from Pocholo Goitia’s An Introduction to the Luminescent [2] and the undescribed time travel method used in Michael A.R. Co’s Waiting for Victory [3]). Wherever possible I have included links to the stories or to discussions about them.

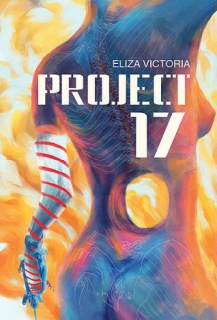

- The SentryServ Identity Database from Project 17 by Eliza Victoria [4]. In Victoria’s

arresting 2013 near-future novel, a shadowy corporation called Sentry keeps track of all humans (and androids), collecting movement, personal records and other important, supposedly private information. This potentially sinister application of technology is probably very close to becoming reality (a few would argue that its already here with Facebook, Google, Tencent and WeChat). Here’s an article on Business Insider on 12 ways that companies spy on you.

arresting 2013 near-future novel, a shadowy corporation called Sentry keeps track of all humans (and androids), collecting movement, personal records and other important, supposedly private information. This potentially sinister application of technology is probably very close to becoming reality (a few would argue that its already here with Facebook, Google, Tencent and WeChat). Here’s an article on Business Insider on 12 ways that companies spy on you.

- Bio-Plasticine Millet and other artificial food from Milagroso by Isabel Yap

(2015) [5]. A balikbayan returns to his childhood home in Lucban Quezon and discovers that artificial, plastic-derived food was somehow being turned into the real thing. This concept of non-nature created food first appeared in an earlier story by the same author, called A List of Things We Know (2013) [6]. Edible plastic as a source of nutrition is also used in my story Blessed Are The Hungry (2014) [7]. The technology of artificial food is a growing new industry. Here are 19 food items that are actually not made from food.

(2015) [5]. A balikbayan returns to his childhood home in Lucban Quezon and discovers that artificial, plastic-derived food was somehow being turned into the real thing. This concept of non-nature created food first appeared in an earlier story by the same author, called A List of Things We Know (2013) [6]. Edible plastic as a source of nutrition is also used in my story Blessed Are The Hungry (2014) [7]. The technology of artificial food is a growing new industry. Here are 19 food items that are actually not made from food.

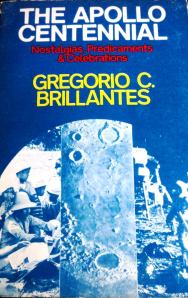

- The Heliodisc VTOL Aircraft from The Apollo Centennial by Gregorio Brilliantes [8]. In this

dystophian short story from 1980, the Marcos dictatorship never fell, and Luzon (now a protectorate of the United States) is patrolled by these unusual VTOL aircraft: “Now the sky is clear but for the remote clouds and a couple of helidiscs humming in a wide arc over the fields. For a moment the fighter-bombers hang gleaming, in silhouette against the mountains, their two-man crews visible in the bubble canopies, before rising vertically, abruptly, cut off from view by the roof of the bus.” It’s interesting how Brilliantes’ fictional aircraft seems to describe the Avro Canada VZ-9 Avrocar, a proposed “UFO” fighter which was still classified when the story was written. A similar egg-shaped VTOL vehicle called an “Aerocopter” also figures in Crystal Gail Koo’s The Rooftops of Manila (2009), this time as a civilian transport to a new underground city.[9]

dystophian short story from 1980, the Marcos dictatorship never fell, and Luzon (now a protectorate of the United States) is patrolled by these unusual VTOL aircraft: “Now the sky is clear but for the remote clouds and a couple of helidiscs humming in a wide arc over the fields. For a moment the fighter-bombers hang gleaming, in silhouette against the mountains, their two-man crews visible in the bubble canopies, before rising vertically, abruptly, cut off from view by the roof of the bus.” It’s interesting how Brilliantes’ fictional aircraft seems to describe the Avro Canada VZ-9 Avrocar, a proposed “UFO” fighter which was still classified when the story was written. A similar egg-shaped VTOL vehicle called an “Aerocopter” also figures in Crystal Gail Koo’s The Rooftops of Manila (2009), this time as a civilian transport to a new underground city.[9]

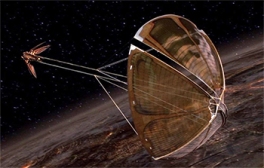

- The Solar sails used by Skyharvester spaceships from Sky Gypsies by Timothy James

M. Dimacali (2007). This story is about a space-faring Sama-Laut father and his son who gather rare minerals from asteroids using their solar-sailed ship the Karumarga.[10] Solar sails, also called “light sails” or “photon sails”, are a type of spacecraft propulsion using radiation pressure exerted by sunlight on large mirrors. As the author correctly posited, in the near future, these may be the best way for humanity to traverse the solar system. NASA recently announced the first such deployment of a solar sail, the Near-Earth Asteroid Scout probe, which will be launched in 2018.

M. Dimacali (2007). This story is about a space-faring Sama-Laut father and his son who gather rare minerals from asteroids using their solar-sailed ship the Karumarga.[10] Solar sails, also called “light sails” or “photon sails”, are a type of spacecraft propulsion using radiation pressure exerted by sunlight on large mirrors. As the author correctly posited, in the near future, these may be the best way for humanity to traverse the solar system. NASA recently announced the first such deployment of a solar sail, the Near-Earth Asteroid Scout probe, which will be launched in 2018.

- Diseases as a Service – In A Retrospective of Diseases for Sale by Charles Tan

(2009) [11], the author goes one step beyond disease mongering with a corporation that sold ailments online (instead of the pharmaceuticals to treat them). The most interesting — and original — part of this concept was how the disease was alleged to be delivered: the vector was the email confirming purchase which contained an encrypted psychosomatic code which could “mentally activate various proteins in the human body that replicated the effects of the disease you ordered.” While no government would allow such a service to operate, it is not impossible to speculate that deadly diseases are already being bought and sold by criminals and terrorists on the Dark Web today.

(2009) [11], the author goes one step beyond disease mongering with a corporation that sold ailments online (instead of the pharmaceuticals to treat them). The most interesting — and original — part of this concept was how the disease was alleged to be delivered: the vector was the email confirming purchase which contained an encrypted psychosomatic code which could “mentally activate various proteins in the human body that replicated the effects of the disease you ordered.” While no government would allow such a service to operate, it is not impossible to speculate that deadly diseases are already being bought and sold by criminals and terrorists on the Dark Web today.

- Xenotransplantation – In 1959’s The Heart of Mathilda (Ang Puso ni Matilde) by

Nemesio E. Caravana [12], a brilliant young surgeon saves the life of his beloved by performing a dangerous and unethical cross-species heart transplant. Xenotransplantation is the transplantation of living cells, tissues or organs from one species to another. Although it is a promising avenue for treating final-stage organ failure, the technology is fraught with ethical issues — not the least of which is the creation of hybrid monsters (which was the subject of this very early Filipino Science Fiction serialized novel). Here’s a brief history of this controversial technique.

Nemesio E. Caravana [12], a brilliant young surgeon saves the life of his beloved by performing a dangerous and unethical cross-species heart transplant. Xenotransplantation is the transplantation of living cells, tissues or organs from one species to another. Although it is a promising avenue for treating final-stage organ failure, the technology is fraught with ethical issues — not the least of which is the creation of hybrid monsters (which was the subject of this very early Filipino Science Fiction serialized novel). Here’s a brief history of this controversial technique.

- Experimental Gerontology – Life extension and human augmentation seems to be a

favorite topic of many Filipino Science Fiction authors. Practically every available SF book in the Philippine oeuvre has at least one story that uses it as a trope. In fact, the earliest known Filipino Science Fiction story, 1945’s Doktor Satan by Mateo Cruz Cornelio [13] involves the development of a serum that could restore the freshly dead back to life. A similar formula called Bio Regain was the subject of Vince Torres’ 2013 short story, The Cost of Living [14] which gave those who drank it a lust for life-extending blood. Interestingly, there is a controversial medical technique called Parabiosis which temporarily connects the circulatory system of an old and a young subject to rejuvenate an old person’s body with youthful blood. The Starvation Enzyme in F.H. Batacan’s brilliant Keeping Time (a short story and later a novel)[15], originally from 2007, also falls under this category. The enzyme was originally developed as a means to control obesity and diabetes. It was added to the world’s public water systems to disastrous consequences. Similarly, in Sharmaine Galve’s The Paranoid Style (2009), the public water supply is tainted with a drug cocktail like to those used to treat ADHD patients. This converts the unsuspecting populace into literally a “polite” society [16].

favorite topic of many Filipino Science Fiction authors. Practically every available SF book in the Philippine oeuvre has at least one story that uses it as a trope. In fact, the earliest known Filipino Science Fiction story, 1945’s Doktor Satan by Mateo Cruz Cornelio [13] involves the development of a serum that could restore the freshly dead back to life. A similar formula called Bio Regain was the subject of Vince Torres’ 2013 short story, The Cost of Living [14] which gave those who drank it a lust for life-extending blood. Interestingly, there is a controversial medical technique called Parabiosis which temporarily connects the circulatory system of an old and a young subject to rejuvenate an old person’s body with youthful blood. The Starvation Enzyme in F.H. Batacan’s brilliant Keeping Time (a short story and later a novel)[15], originally from 2007, also falls under this category. The enzyme was originally developed as a means to control obesity and diabetes. It was added to the world’s public water systems to disastrous consequences. Similarly, in Sharmaine Galve’s The Paranoid Style (2009), the public water supply is tainted with a drug cocktail like to those used to treat ADHD patients. This converts the unsuspecting populace into literally a “polite” society [16].

- Cybernetic Augmentation – The other way to extend life is to go the Transhumanist

route of using Bionics. In Fortitude (again by Eliza Victoria, 2016) [17], many characters live with cybernetic transplants including arms and lungs. In Dancing in the Shadow of the Once (2013) by Rochita Loenen-Ruiz [18], a woman uses media-based augmentations to recount the stories of a world that was now lost. Dominique Gerald Cimafranca’s 2007 story Facester, revolves around a procedure called “Cara Nuevo” that used an artificial enzyme, laser sculpting and radiation treatments to let people physically change their faces [19]. Naturally, identity theft was one of the inevitable unfortunate applications. Here’s an article about a few individuals who have gone beyond wearable technology towards a post-human future. For those not inclined to replacing body parts with electronics, there is the somewhat less radical practice of bio-hacking.

route of using Bionics. In Fortitude (again by Eliza Victoria, 2016) [17], many characters live with cybernetic transplants including arms and lungs. In Dancing in the Shadow of the Once (2013) by Rochita Loenen-Ruiz [18], a woman uses media-based augmentations to recount the stories of a world that was now lost. Dominique Gerald Cimafranca’s 2007 story Facester, revolves around a procedure called “Cara Nuevo” that used an artificial enzyme, laser sculpting and radiation treatments to let people physically change their faces [19]. Naturally, identity theft was one of the inevitable unfortunate applications. Here’s an article about a few individuals who have gone beyond wearable technology towards a post-human future. For those not inclined to replacing body parts with electronics, there is the somewhat less radical practice of bio-hacking.

- Robot Companions – Robots are no longer Science Fiction and scientists are looking

at augmenting them using Artificial Intelligence (AI) to provide empathy and assistance to people in a socially acceptable manner. The question that both Science Fiction and Technology writers have asked is: how human do these machines need to be? Also, how far can or should people take relationships once the so-called Uncanny Valley is crossed? In Haya Makes a HUG by Erica Gonzales (2009), a sentient program tries to find out what a human hug means by building a humanoid from spare parts. [20] In Raymond P. Reyes’ The Romeo Robot (2016), a spoiled but lonely young man begs his father for a robot boyfriend only to abandon his faithful companion once his social anxiety is overcome. [21] Likewise, in Surrogate (2016) by Daniel Carlos Tan, a young woman from a future Davao cannot handle the fact that her recently deceased mother had programmed herself into a Personal Surrogate Droid.[22] Here’s an article exploring the future of relationships, love and sex in the time of robots.

at augmenting them using Artificial Intelligence (AI) to provide empathy and assistance to people in a socially acceptable manner. The question that both Science Fiction and Technology writers have asked is: how human do these machines need to be? Also, how far can or should people take relationships once the so-called Uncanny Valley is crossed? In Haya Makes a HUG by Erica Gonzales (2009), a sentient program tries to find out what a human hug means by building a humanoid from spare parts. [20] In Raymond P. Reyes’ The Romeo Robot (2016), a spoiled but lonely young man begs his father for a robot boyfriend only to abandon his faithful companion once his social anxiety is overcome. [21] Likewise, in Surrogate (2016) by Daniel Carlos Tan, a young woman from a future Davao cannot handle the fact that her recently deceased mother had programmed herself into a Personal Surrogate Droid.[22] Here’s an article exploring the future of relationships, love and sex in the time of robots.

- Digital Torture – As a predominately Catholic country, the subjects of Heaven and

Hell are never far from the minds of most Filipinos. In my story Panopticon (2014) I explored the possibility of being trapped in a digital afterlife, tortured endlessly by a vengeful former lover.[23]. The Technological Singularity may still be faraway but using neural interfaces for recreating the proverbial tortures of hell is rapidly becoming a reality. “Remote Neural Monitoring, Control and Manipulation” (RNMCM) refers to the usage of specific technologies to record and/or alter the electrical activity of neurons in the human body. In Prisoner 2501 by John Philip Corpuz (2011), the Olympus MetroComm of an unnamed dystophian future city use RNMCM, gaslighting and isolation to torture prisoners into admitting terrorist affiliations. Elon Musk, a major proponent of neural interfaces, has spoken against the abuse of this technology for this type of interrogation.

Hell are never far from the minds of most Filipinos. In my story Panopticon (2014) I explored the possibility of being trapped in a digital afterlife, tortured endlessly by a vengeful former lover.[23]. The Technological Singularity may still be faraway but using neural interfaces for recreating the proverbial tortures of hell is rapidly becoming a reality. “Remote Neural Monitoring, Control and Manipulation” (RNMCM) refers to the usage of specific technologies to record and/or alter the electrical activity of neurons in the human body. In Prisoner 2501 by John Philip Corpuz (2011), the Olympus MetroComm of an unnamed dystophian future city use RNMCM, gaslighting and isolation to torture prisoners into admitting terrorist affiliations. Elon Musk, a major proponent of neural interfaces, has spoken against the abuse of this technology for this type of interrogation.

One of the troubling aspects about chronicling the ten technologies above (and reading the twenty-three stories where they were used) is that these were all presented in a more or less negative context. There is little of the positive world view in which scientific progress has made the world a better place. Whether this is due to: an innate fear of technology, a reflection of the zeitgeist, or simply that there are not enough Filipino Science Fiction stories yet — or, perhaps all three — is up for debate.

There is also that unique fear that plagues Science Fiction writers. Namely, that their stories will be judged on whether what they wrote comes to pass or not, with no thought to literary merit. This is a mistaken notion. The task of Science Fiction is not to predict the future. Rather, it is to contemplate all possible futures. Simply put, Filipino Science Fiction Writers are meant to dream of every future for Filipinos.

For now, it’s a dark future that many of us are dreaming.

Notes:

[1] Davenport, Basil (1955). Inquiry Into Science Fiction; New York: Longmans, Green and Co. p. 15.

[2] Goitia, Pocholo (2005) “An Introduction to the Luminescent”. Philippine Speculative Fiction Volume 1, ed. Alfar, Dean Francis; Manila: Kestrel DDM

[3] Co, Michael A.R. (2006) “Waiting for Victory”. Philippine Speculative Fiction Volume 2, ed. Alfar, Dean Francis; Manila: Kestrel DDM

[4] Victoria, Eliza (2013) Project 17; Manila; Visprint Inc.

[5] Yap, Isabel (2015) “Milagroso“; Tor.com published by Tor Books

[6] Yap, Isabel (2013) “A List of Things We Know”, Diaspora Ad Astra: An Anthology of Science Fiction from the Philippines eds. Flores, Emil M. & Nacino, Joseph Frederic F. ; Manila, The University of the Philippines Press

[7] Ocampo, Victor Fernando R. (2014) “Blessed Are The Hungry“, Apex Magazine vol. 62, ed. Sigrid Ellis; Lexington; Apex Book Company

[8] Brilliantes, Gregorio C. (1980), “The Apollo Centennial”, The Apollo Centennial: Nostalgias, Predicaments & Celebrations; Manila, National Bookstore

[9] Koo, Krystal Gail “The Rooftops of Manila”(2009), Philippine Speculative Fiction Volume 4, eds. Alfar Dean Francis & Alfar, Nikki; Manila, Kestrel DDM

[10] Dimacali, Timothy James M. (2007) “Sky Gypsies“; Manila, Philippine Speculative Fiction Volume 3 eds. Alfar Dean Francis & Alfar, Nikki, Kestrel DDM

[11] Tan, Charles (2009), “A Retrospective of Diseases for Sale“; The Virtuous Medlar Circle presented by Anna Tambour. Also appears on Philippine Speculative Fiction Volume 4, eds. Alfar Dean Francis & Alfar, Nikki; Manila, Kestrel DDM

[12] Caravana, Nemesio E. (1959), The Heart of Mathilda (Ang Puso ni Matilde); Manila, Aliwan Magazine

[13] Cornelio, Mateo Cruz (1945) Doktor Satan; Manila, Palimbagang Tagumpay

[14] Torres, Vince (2013), “The Cost of Living”; Diaspora Ad Astra: An Anthology of Science Fiction from the Philippines eds. Flores, Emil M. & Nacino, Joseph F. ; Manila, The University of the Philippines Press

[15] Batacan, F.H. (2007) “Keeping Time“, Philippine Speculative Fiction Volume 3, eds. Alfar, Dean Francis & Alfar, Nikki; Manila, Kestrel DDM

[16] Galve, Sharmaine “The Paranoid Style”(2009) Philippine Speculative Fiction Volume 4, eds. Alfar Dean Francis & Alfar, Nikki; Manila, Kestrel DDM

[17] Victoria, Eliza “Fortitude” (2016) Science Fiction: Filipino Fiction for Young Adults eds. Alfar, Dean Francis & Yu, Kenneth; Manila, University of the Philippines Press

[18] Loenen-Ruiz, Rochita, “Dancing in the Shadow of the Once” (2013) Bloodchildren: Stories by the Octavia Butler scholars, ed. Nisi Shawl; Seattle, Book View Cafe

[19] Cimafranca, Dominique Gerald, “Facester” (2007) Philippine Speculative Fiction Volume 3, eds. Alfar Dean Francis & Alfar, Nikki; Manila, Kestrel DDM

[20] Gonzales, Erica, “Haya Makes a HUG” (2009) Philippine Speculative Fiction Volume 4, eds. Alfar Dean Francis & Alfar, Nikki; Manila, Kestrel DDM

[21] Reyes, Raymond P. ,”The Romeo Robot” (2016) Science Fiction: Filipino Fiction for Young Adults eds. Alfar, Dean Francis & Yu, Kenneth; Manila, University of the Philippines Press

[22] Tan, Daniel Carlos ,”Surrogate” (2016) Science Fiction: Filipino Fiction for Young Adults eds. Alfar, Dean Francis & Yu, Kenneth; Manila, University of the Philippines Press

[23] Ocampo, Victor Fernando, “Panopticon” (2009) Philippine Speculative Fiction Volume 9, eds. Drillon, Andrew & Tan, Charles; Manila, Kestrel DDM

[24] Corpuz, John Philip, “Prisoner 2501” (2011) Philippine Speculative Fiction Volume 6, eds. Alfar, Nikki & Osias, Kate; Manila, Kestrel DDM

Top image reworked slightly from original digital art by BP Sola. All other pictures taken from the Internet and belong to their respective copyright owners.